The Professional World of Ira Arthur Moore

Maude Annabelle Castner

From Howard O. Paige's letter of

No boy ever had a more loving, devout, seemingly tireless mother. A true homemaker who would always put her family first ahead of all else. When money was short she took on dressmaking for some of the elite women in town to earn and help keep the family going. I can still see her bending over the weekly washboard with a bar of Fels Naptha soap in her hand doing the family washing. There was a woodshed built on the back of our house and under the floor about 2 feet down was a deep cistern into which rainwater from the roofs was piped for use in washings where "soft" water was needed. It was quite dirty and smelly but served nicely for the purpose. There were no washing machines in those days and no water softeners except some powders such as Borax sold for that purpose. The cistern, covered with boards, was a deep spooky mystery to us kids.

Wash day called for a large copper boiler to be put on the kitchen gas stove reaching over two burners to be filled with rainwater from the pitcher pump in the nearby kitchen sink. No hot water heaters yet either! Then there was a special rack that held two wash tubs on opposite ends with a hand wringer in between so clothes could be wrung through to get out the soapy water and into the rinse tub and then back onto a flat board thence to go outdoors onto the clothes' line. Some women took in washings to earn money to live on; it was sure doing things the hard way! I can still see Mom working over that scrub board and hoping we would be near to turn the ringer for her, not our favorite pastime, believe me. She often hung the clothes outdoors to freeze, she said they smelled so nice; she didn't mention her frozen hands! From her meager income she was able to purchase a new violin for me from Grinnell Bros. and paid one dollar a week for me to take lessons from the then popular Max Helmer.

Mom

and Dad separated when I was about 14, and she took a job selling shoes first

at Stillman's, then at the Walkover Shoe store, which

was later taken over by Rackleys. Ed Rackley wor

Additional information about the marriage, married years, divorce, and post-divorce years of Charles Orlando Page and Maude Annabelle (Castner) Page can be found at Castner_Family_p4.html, Sarah_Keyes.html and In_Search_of_Riley.html.

Additional information about Charles Orlando Page’s life can be found at Sarah_Keyes.html, including his marriage to Florence (Peck) Squier, at In_Search_of_Riley.html and Charles_and_George_Page.html.

Additional information about Maude Annabelle (Castner) Page can be found at Castner_Family_p4.html, Sarah_Keyes.html and In_Search_of_Riley.html.

Later

in life Mom met and married Ira A. Moore, an assistant steward at the Jackson

Prison. They built a new home on

Maudie had little money during her first sixty years. She had to work hard to make ends meet. It wasn't until after her second marriage that Maudie could begin living the way she wanted. Then she also began salting money away to safeguard against a penniless old age, destitution being a problem she had seen time and again in her own family.

I don't remember too much about the divorce between Mom and Dad (we called him 'Pop'). Mom seemed never quite satisfied with the money available and did sewing on the side for well-to-do customers.

Because

there was talk, and accusations were made at divorce time, some of it hearsay,

the whole true picture is not clear. Dad (apparently) wanted to go to

Mom

went to work in Stillman's shoe department, and I wor

Dad

would come to Grandma's house on

After Maudie's first marriage

ended in about 1923, she and the children continued on temporarily in the house

at

Maudie's ex-husband Charles Page died in 1941. Also that

year she met Ira Arthur Moore, a son of Jacob and Clarinda Jane (Duff) Moore. Ira had been a farmer in

The Professional World of Ira Arthur Moore

Picture created by W. M. Nott at SPSM

The following article appeared in the

SPSM’s Steward Rules Large Domain

By

Conrad Payne

The way to a man’s heart is through his stomach. This is even more true in prison than elsewhere. The most recalcitrant and obstreperous prisoner beams happily over a good meal.

With this precept constantly in mind, Ira A. Moore, robust chief steward, rules his domain with zealous fervor. His chief concern is to please the main line—everything else is of secondary importance, even the officers’ dining room.

How well he succeeds fluctuates according to varied tastes and appetites of inmates, which are more varied than the offenses for which they were committed.

This

situation makes steward

A

southerner is fond of corn meal muffins, fat meat and collards; a Bostonian

raves over ba

Because

of such diversity it is impossible to please every one at the same time.

How

formidable such a job can become is readily understood when it is realized that

during the course of one week Moore serves enough meals to feed every man,

woman and child in the entire county of Jackson, including the city of

There

is another vital factor which influences the degree to which

Many years ago it was the practice to allow so much per day per inmate. In fact one hundred years ago, in 1855, inmate meals per day were limited to a value of six and a half cents.

Today

the budget allowance is estimated after a careful study and based on many

considerations.

There

are nineteen stewards who work under

At

the hospital kitchen, there are an additional 30 men and one commissary clerk;

four kitchen workers at the Vandercook Farm; ten at

This

is the empire

He

started to work as a guard at SPSM on

In

the spring of 1943 he began working as a steward, was confirmed

Next week: What makes the Kitchen tick.

The following article

appeared in the

What Makes The Kitchen Tick?

By

Conrad Payne

SPSM’s kitchen serves six million meals a year—that’s a record of some kind, for few commercial establishments do a business of such magnitude. Reflected in dollars it amounts to approximately one million a year. Ira A. Moore, chief steward, administers this Herculean job efficiently and competently.

Every

ounce, every pound of these millions of meals requires careful and accurate

charting and tabulating, and hundreds of records must be kept current daily,

with monthly and annual inventory thrown in for good measure. Into this job

steps “Pappy”

Watson

bring his skill and ability to these tasks and

relieves the chief steward of the vast majority of tedious and irksome details.

Not all this work, of course, is done by Watson. He has a battery of excellent

helpers, such as Bobby Falkensteiin of

Watson

is a husky Irishman, with close-cropped, prematurely grey hair, a token of his

prison years. He was born in

For

relaxation, Watson avidly reads “who-dun-its” and sometimes goes through two or

three books and magazines in a single day. He is one of those unique

individuals who, to use the words of the boss Chief Steward Moore, “If he wor

Now for the food, without which the kitchen would be in sad shape. Just for one month’s meals here is a partial list of the quantities used:

Beef, 64,067 pounds; Pork, 55,237 pounds; American cheese, 4,665 pounds; eggs, 405,930; flour, 97,650 pounds; coffee, 12,849 pounds; milk, 220,241 pounds; potatoes, 180,706 pounds; granulated sugar, 23,048 pounds; corn sugar used in baking, 5,300 pounds; brown sugar, 7,035 pounds; powdered sugar, 4,837 pounds; oatmeal, 1,278 pounds; saltine crackers, 5,746 pounds; oleo-margarine, 7,672 pounds; Jello, 1,540 pounds; chili beans, 3,485 pounds; macaroni, 2,220 pounds; navy beans, 5,974 pounds; spaghetti, 2,800 pounds; noodles, 1,030 pounds; and peanut butter, 3,150 pounds.

This gives a little idea of what huge quantities the kitchen force handles monthly. There are a lot of other items, too, such as 62,943 loaves of bread; 3,850 pounds of corn flakes; 1,222 pounds of rice krispies; 805 pounds of maltex; 548 pounds of farina; 6,994 pounds of fish.

In the canned foods, all in number 10 cans, there are such items as 2,509 cans of tomatoes; 1,528 cans of peaches; 1,259 cans of cherries; and 1,763 cans of tomato puree.

To prepare all this food is a never ending job, and the chief cook, Jim Burbank, and the shift cooks under him Maddox and Henning, have more than their share of headaches. Few envy them their job, and in cooking in tremendous quantities, even the best of food loses something of its flavor and texture.

There is always somebody grumbling about the food, this writer as much as anyone, but the cooks have a tough time of it to meet the insatiable appetites of the main liners, and the definite deadline for the meal-hours. Actually these boys are doing a grand job, all things considered, for it is a thankless task, and never any bouquets.

There

is almost continuous, round the clock serving of meals. Starting at

Occasionally, after menus have been made out, a little thing like non-delivery or delayed delivery of certain items will raise havoc with the menu arrangement, and there is a frantic rush to make last minute changes and still keep from duplicating a meal previously served within the week.

Despite the fact that the institution has large areas of farm land that produces large quantities of produce, and a canning factory that turns out an annual production comparable with many canneries in the civilian world, every item the kitchen gets from farms or cannery must be paid for from the budget allowance. This appears to be taking money out of one pocket and putting it into another, and, of course that is exactly what happens, but it is the only way to keep all accounts straight and up to now no one has thought of a better system.

Back in 1932 the kitchen was equipped with five 100-gallon coffee urns, six 100-gallon aluminum steam kettles, six iron roasting pots with a 75 gallon capacity each 46 vegetable cookers with a capacity of one bushel each, and a 3 oven bakeshop with a capacity for 17,000 loaves of bread monthly.

At

the same time the dining room was equipped with four steam tables, and divided

into two separate sections 104 by 160 feet, each. There was 45,000 pieces of

equipment washed and stac

There

have been many changes since that time, some for the better. For example there are now six 100-gallon coffee urns, two bright new ones just

put into operation. There are 12 100-gallon steam kettles; 24 double vegetable

cookers; six stainless steel food heaters; and 12

Back in the milk room there are two bright, gleaming Cherry-Burrell spray pasteurizers equipped with Sentinel temperature controls and circular graph recorders on each. There is a double unit homogenizer with pre-filter attachments. In the same room is a butter cutter, and in an adjacent room there is a three-wash combination live steam and water rinse for cleaning milk cans thoroughly.

In the ice cream room there is a large ice cream machine that furnishes all the ice cream used by the institution. When this machine goes on the fritz, ice cream production is curtailed and there is no ice cream for the Sunday evening meal or the holiday meal until the machine is repaired. Just recently a new ice cream formula was tried which improved the quality of the ice cream to an amazing degree. The full story about the ice cream formula change was reported in the Spectator at the time it occurred.

To

get an idea of the growth of the State Prison of Southern Michigan one has only

to look at the amount of bread ba

Any way you look at it, the feeding of more than six thousand men is a big job, as well as a complicated one. It is the same old grind meal after meal, day after day, week after week, and year after year. It never ends. There is no such thing as getting the work caught up and taking a breather or a rest. It requires a lot of drive with plenty of energy on the part of the entire force to just stay abreast of the demand for service. A slip-up anyplace along the line can create untold havoc.

Feeding the inmate population at SPSM is a gargantuan task, there is nothing easy about it. And the man to whom we can give the lion share of the credit for the meals turned out on an almost production line basis is none other than the chief steward, Ira A. Moore, for he makes them what they are.

The following article

appeared in the

SMP Chief Steward Ends 29-Year Tenure

Ira A. "Pappy" Moore, who since 1952 has been putting out 18,000 meals daily for the inmates at Southern Michigan prison, hung up his apron and put away his calorie chart Thursday, ending 29 years of service at the institution.

He was honored at a luncheon in the prison officers dining room Thursday.

Mr.

Moore, who lives at 210 E. Palmer, was born in September, 1886, on a farm in

Carroll county,

He began as a guard at the local institution and served in a number of assignments, chiefly in the dining room. In 1940 he was named assistant steward and immediately after the riot in 1952 he was named chief steward.

Pappy has served under nine wardens at the prison beginning under Harry Jackson. In his 29 years of service at the institution he has been absent because of sickness on only one day.

As chief steward, Mr. Moore has supervised the daily preparation of meals in the large prison kitchen, within the walls, the hospital kitchen, the 16 block kitchen and the five kitchens on the trustee farms.

Mr.

Moore plans to move to

The following article

appeared in the

George Scofes Replaces ‘Pappy’ As Kitchen Boss

George Scofes

of

Scofes is a graduate of

He was assigned as a mess officer and was responsible for feeding 7000 men.

The restaurant business is not new to

the new steward; his family owns the Famous Grill in

“They knew their jobs,” Scofes said, “They were good workers and never gave us a minute’s trouble.”

At the present time, Scofes is getting acquainted with the operating procedure of the institution. He has been meeting the 19 stewards and many of the 500 inmates on the kitchen assignment.

“I wouldn’t want anyone to hire me for a job like this and say, ‘here it is, goodbye.’”

When

as

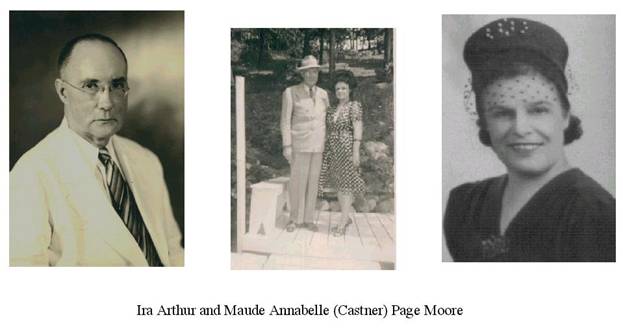

Maudie and Ira Moore

Maudie and Ira were married at

Maudie loved Ira deeply, and the two kindred souls took

good care of each other. During most of their 22 years together they were

inseparable, traveling extensively in their sequence of Chryslers, and jaunting

occasionally between

A bout with

free association regarding the Moores, and especially

Grandma Maude, produces in me an impression of an endless supply of cake and

ice cream, coffee, lemon drops, Chiclets gum, Mogen

Maudie's freedom was curbed after her mother fell and broke

her arm in the late 1950s. The aged, convalescing Frankie was requiring more

time and attention. Then things seemed to brighten once more when Ira, who was

affectionately called "Pappy" by the inmates, retired as head chef of

the State Prison of Southern Michigan in January of 1958. The

Ira had been overweight in his later years. In 1959 the condition helped precipitate uremia. The sickness, in its various stages, robbed him of his strength. A number of hospitalizations were required, and when he was home there was a virtual mountain of pills to take. Maudie watched helplessly as his life became painful and demoralized.

By 1962 Ira

was feeling better. In the autumn Maude's cherished and only niece Laronge (Castner) Brann came from

Maude was

torn between satisfying the needs of her mother and of her husband. She was

finally able to have Ira transferred to

Maudie's shock and grief over the losses dulled her mind, and the next years were spent in a post-trauma daze. The death of her niece Laronge in 1965 added another weight. A poem she wrote expresses how Maude reconciled the long years of awaiting death with the transcendental joy of expecting new life:

-To Ira-

To what far distant land

He has taken his way?

Pack the shadows of

night--

There has dawned a new day.

And this be my comfort

Through grief hard to bear.

That far country is 'home,'

And he waits for me there

In memory of poor Ira, who wanted to stay and look after me. -Maude

The After Years

"I always sensed Maudie and Margaret in a different world . . .. more spiritual might partially describe it. I even felt part of Maudie's world—can't hardly describe the feeling.... Margaret, Maudie and myself were egotistical perhaps in some ways more vital, more mentally intense, less anchored to solid acceptance, more inclined (on my part at least) to enjoy wandering up and down mental frontiers." H. O. Paige's letter of August 1981

Maudie had never been particularly religious, although she

and daughter Margaret had sung in the choir at

Maudie was in no hurry to live in the New Moon--she could

have felt that the new residence was a step away from her secure world and

toward one of oblivion in a nursing home. She would go out occasionally to

"visit" the trailer, but didn't stay long. In the meantime her sons

kept things in order at her house. However, her independence was reduced by a

fall she had in the mid-1960s. Maudie was over 80

years old when she slipped on the grass at her

The fall hurt

Maudie's back, and she was admonished by her doctor

against doing such strenuous work in the future. She was told to wear a special

garment to help the back condition. But stubbornly she refused to wear it

except on certain occasions, and then only if coerced. As the years passed her

height mar

Maude now had to spend more time at the New Moon so Esther could look after her. But where Maudie was, so was the Ouija board. Her bouts with the occult grew more frequent. She used the information divined to explain things happening around her. All attempts by Howard and Marshall to separate her from the board failed. Then one day, in a fit of terror, she burned it.

A neighbor

girl used to come over to be with Maudie in the

afternoons and evenings she spent on

As the new

decade of the 1970s dawned, it found Maudie in her

waning years. She was more frequently bedridden. And it became apparent that

she wouldn't duplicate her mother's life span. On

And this be my

comfort

Through grief hard to bear.

That far country is

'home,'

And he waits for me there.

Copyright 1982, 2010 Charles W. Paige

Return

to Castners: Ed and Frankie leave Ovid

Return

to the Page and Castner Families table of contents

Last modified: Tuesday, July 27, 2010